News Center

News Details

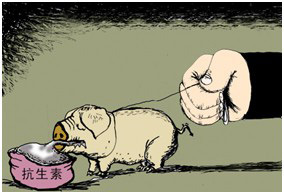

Antibiotic use in feed: yes or no

Release time:

2014-09-17 00:00

Source:

Antibiotics were once a revolution in animal husbandry, significantly reducing animal disease rates and ensuring the growing demand for meat. Although the direct toxicity of antibiotic residues in animals to humans is minimal, drug-resistant bacteria in animals can be transmitted to humans through air, wastewater, and soil. In the future, if bacterial infections occur, they may be untreatable.

In the United States, buying antibiotics is harder than buying a gun.

This popular saying should include a qualifying phrase—for humans. For animals, the supply of antibiotics is virtually unrestricted. There is no need for illness, nor a veterinarian's prescription; simply to promote animal growth, farmers can buy antibiotics and mix them into feed and water. According to a widely cited set of data, nearly 80% of antibiotics in the United States are used in animal farming. The amount of antibiotics used in animal farming is four times that used in human medicine. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is determined to change this situation: On December 11, 2013, it issued a guiding document to restrict the misuse of antibiotics in animal farming, especially prohibiting antibiotics as feed additives to stimulate animal growth.

Time Bomb

As one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century, antibiotics helped humanity overcome once invincible bacteria, increasing average human lifespan by 10 years. When zoologists accidentally discovered in the 1950s that it also promoted animal growth and prevented disease, it brought about a revolution in global animal husbandry. Numerous studies have confirmed that adding antibiotics to feed increases animal growth rate and feed utilization by 5% to 10%. For 60 years, no one knew why antibiotics could accelerate animal growth. Scientists speculate that antibiotics help animals prevent low-level diseases and improve their nutrient absorption systems, thereby promoting growth. Microbiologist Brether of New York University believes that these drugs cause bacteria to absorb heat more frantically, leading to rapid weight gain. After the FDA first approved the use of antibiotics as feed additives in 1950, antibiotics were widely used as growth promoters, significantly reducing the production costs, incidence, and mortality rates of animal farming.

Thereafter, healthy animals were also fed antibiotics to increase growth rate and prevent diseases caused by intensive farming practices. Intensive farming practices have greatly improved the efficiency of animal husbandry, but overcrowded and unsanitary environments have also increased the risk of animal infectious diseases. Antibiotics enabled farms to restrict livestock space and activity while maintaining animals in optimal health. Without antibiotics, intensive livestock systems might not have become a profitable production model. From then on, the modern farming system gradually fell into a predicament of dependence on and abuse of antibiotics—drugs originally used to treat diseases became a production tool. At one point, animal husbandry consumed half of the world's antibiotics.

Although the application of antibiotics has promoted the development of animal husbandry, allowing more people to buy more meat products at low prices, it has brought about a global health crisis—the death threat posed by the prevalence of drug-resistant bacteria. According to Hu Bijie, director of the Hospital Infection Control Society of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association, approximately 500,000 people in China die each year due to bacterial resistance. Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that more than 2 million people in the United States fall ill each year due to infections with drug-resistant bacteria, with 23,000 deaths from drug-resistant bacterial infections. Drug-resistant bacteria were not born so powerful; in fact, it is man-made. It is the misuse of antibiotics by humans that has created the drug resistance of bacteria.

In fact, from the first day antibiotics were used, their power against bacteria has been weakening. Organisms need to survive their species, so they need to develop resistance to external harm. For bacteria, this is resistance to antibiotics. The goal of scientists is to develop new drugs to replace those that are gradually becoming ineffective while maintaining the effectiveness of existing antibiotics as much as possible. Unfortunately, bacterial resistance is becoming stronger. Developing a new antibiotic takes ten years, while rendering that new antibiotic ineffective takes only two years.

The misuse of antibiotics in both medical and animal husbandry fields has exacerbated the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. "Human use in the medical field has contributed to this, but animal husbandry is equally culpable." In the United States, the amount of antibiotics used to treat diseases is far less than that used on animals. In 2011, more than 13,600 tons of antibiotics were used in animal farming, while the amount used to treat human diseases was 3,600 tons. China is also a major antibiotic producer. In 2006, China produced 210,000 tons of antibiotics annually, exporting 30,000 tons, of which 97,000 tons—46.1% of annual production—were used in animal husbandry. Seven years later, industry insiders estimated that China's annual antibiotic production had exceeded 400,000 tons. Long-term addition of low doses of antibiotics to animal feed—primarily to stimulate animal growth rather than treat animal diseases—is a very dangerous practice, similar to conducting large-scale experiments on cultivating drug-resistant bacteria in animals.

Scientists at the University of Illinois discovered that bacteria in soil and farmland groundwater acquired tetracycline resistance genes from pig gut bacteria. The dose of antibiotics added to feed as growth promoters is insufficient to kill bacteria; instead, the bacteria's resistance to antibiotics is strengthened, and farms and edible animals are cultivated into a reservoir of drug-resistant genes. According to Southern Weekend, to ascertain the types and presence of antibiotic-resistant genes in pig farming, Zhu Yongguan, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Urban Environment Institute, sampled pig manure from three large pig farms in Beijing, Zhejiang, and Fujian. The Michigan State University laboratory tested these samples and found 149 drug-resistant genes, whose frequency of appearance was 192 to 28,000 times higher than that of the control samples. Although the direct toxicity of antibiotic residues in animals to humans is minimal, drug-resistant bacteria in animals can be transmitted to humans through air, wastewater, and soil, planting a time bomb in the human body. In the future, if bacterial infections occur, they may be untreatable.

Prescription feed

The medical community has long been aware of the rampant antibiotic-resistant bacteria caused by the overuse of antibiotics in animal farming. In 1970, the FDA established a special task force to investigate the relationship between animal farming and bacterial resistance. Led by Dr. Vern Haug, then director of the FDA's veterinary office, the task force conducted a two-year investigation and issued a report in 1972 stating that antibiotic feed additives lead to an increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria in animal intestines, which can spread to humans, increasing health risks. The FDA accumulated substantial evidence and in 1977 submitted a proposal to the US Congress to ban the use of penicillin in animal feed and restrict the use of tetracycline and chlortetracycline. However, this was met with joint opposition from the pharmaceutical industry and farmers. Pharmaceutical companies and animal farming representatives argued that this was an "attack on free enterprise," and that restrictions would significantly increase the cost of animal farming, making it impossible for the livestock industry to meet market demand for meat. Under the dominance of agricultural and pharmaceutical interests, Congress rejected the FDA's proposal on the grounds of "lack of decisive data." According to then-FDA Commissioner Donald Kennedy, there was sufficient evidence at the time to justify restricting antibiotic use, but fierce opposition from the agricultural and pharmaceutical industries led to their defeat in that battle.

Europe, however, took the lead, with Sweden being the first country to act. In 1986, Sweden completely banned the use of antibiotics in animal feed, followed by Denmark. From 2000 onwards, Danish farmers could only purchase antibiotics for treating animal diseases with a veterinary prescription. The strongest ban came from the European Union. From January 1, 2006, all EU member states completely banned the use of antibiotic growth promoters in animal feed. Although this came at a cost, increasing farming costs by 8%-15%. In the first two years, Swedish pig farming consumed at least 70,000 tons more feed, and the incidence of piglet diarrhea increased from 1%-15% to 50%. In the first year of Denmark's ban on antibiotics in animal farming, the incidence of disease in pigs reached an all-time high. However, the situation of antibiotic overuse did improve. In 2004, Sweden's antibiotic use was 65% lower than before the 1986 ban, and Denmark's total consumption of antibiotics in animal farming decreased from 206 tons in 1994 to 102 tons in 2003. The number of Danes infected with antibiotic-resistant enterococci also decreased.

After losing to the pharmaceutical and animal farming industries in 1977, the FDA failed to mount a systematic counterattack for 36 years, only sporadically issuing policies to regulate the use of antibiotics in animals. In 2008, the FDA attempted to restrict the use of cephalosporin antibiotics in animal farming, but again failed due to joint opposition from pharmaceutical companies and the animal farming industry. In 2010, the FDA began publishing the amount of antibiotics used in animal farming. Most antibiotics were used for animals, not for treating human diseases. Due to obstruction from the animal farming industry, the FDA was unclear whether these antibiotics were used to stimulate animal growth or to treat animal diseases. The scales began to tip towards policymakers concerned with public health. When the FDA reintroduced the ban on cephalosporin antibiotics in 2012 (which had been withdrawn in 2008), the resistance was much less. In April of the same year, the FDA introduced non-mandatory measures, suggesting that animal antibiotic producers voluntarily stop selling antibiotics as feed additives to address the current serious crisis of bacterial resistance. Farmers could use antibiotics to prevent and treat animal diseases under veterinary supervision.

The guidance document issued by the FDA this December is an updated version that incorporates feedback from the public and industry. The FDA requires manufacturers of animal antibiotics to rewrite drug labels, removing any mention of growth promotion. Antibiotics will only be allowed for the prevention and treatment of animal diseases. This means that it will become illegal for farmers to continue purchasing antibiotics to stimulate animal growth. Under the FDA's final plan, the purchase of antibiotics will require supervision by a licensed veterinarian. In other words, antibiotics will become prescription drugs.

"This is a sea change," said Michael Taylor, FDA deputy commissioner, "The days of being able to buy antibiotics over the counter at any feed store without oversight are over."

It is worth noting that this guidance document only requests, rather than mandates, that pharmaceutical companies make changes. The two largest manufacturers of animal antibiotics have indicated their willingness to comply with the FDA's new rules, but the FDA has not disclosed the specific company names. Other pharmaceutical companies will inform the FDA within 90 days whether they will implement the new rules. Taylor is quite confident about this, based on previous feedback, that pharmaceutical companies will comply with the new regulations.

"If companies don't comply with the new rules, the FDA will seek other control measures," said Michael Taylor.

However, not everyone is optimistic. Critics worry that the new rules have a fatal flaw. The continued use of low doses of antibiotics mixed into animal feed by the animal farming industry, in addition to stimulating animal growth, is also done for disease prevention. The new rules still allow antibiotics to be used for disease prevention in animals, meaning that the animal farming industry can circumvent the ban and continue feeding antibiotics to healthy animals.

"Even if all antibiotics are banned for stimulating animal growth, many antibiotics can still be used in a similar way," said Keith Naumann, a scientist at Johns Hopkins University, in an interview with the New York Times.

Naumann believes that a more effective measure would be to ban antibiotics for the prevention of animal diseases. This would restrict antibiotics to the treatment of animal diseases, a much smaller scope.

Louise Slaughter, a Democratic congresswoman from New York and the only microbiologist in the US Congress, has been working for years to promote legislation to restrict antibiotic use on farms. She pointed out that the FDA's actions in addressing the crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria caused by the overuse of antibiotics in animal farming are "inadequate." "Sadly, this is the biggest step the FDA has taken in years, but in the face of such an unprecedented public health crisis, it is far from enough."

(—From Nandu Weekly)

Next page